Android Cryptographic APIs

In the chapter Cryptography in Mobile Apps, we introduced general cryptography best practices and described typical flaws that can occur when cryptography is used incorrectly in mobile apps. In this chapter, we'll go into more detail on Android's cryptography APIs. We'll show how identify uses of those APIs in the source code and how to interpret the configuration. When reviewing code, make sure to compare the cryptographic parameters used with the current best practices linked from this guide.

Verifying the Configuration of Cryptographic Standard Algorithms

Overview

Android cryptography APIs are based on the Java Cryptography Architecture (JCA). JCA separates the interfaces and implementation, making it possible to include several security providers that can implement sets of cryptographic algorithms. Most of the JCA interfaces and classes are defined in the java.security.* and javax.crypto.* packages. In addition, there are Android specific packages android.security.* and android.security.keystore.*.

The list of providers included in Android varies between versions of Android and the OEM-specific builds. Some provider implementations in older versions are now known to be less secure or vulnerable. Thus, Android applications should not only choose the correct algorithms and provide good configuration, in some cases they should also pay attention to the strength of the implementations in the legacy providers.

You can list the set of existing providers as follows:

StringBuilder builder = new StringBuilder();

for (Provider provider : Security.getProviders()) {

builder.append("provider: ")

.append(provider.getName())

.append(" ")

.append(provider.getVersion())

.append("(")

.append(provider.getInfo())

.append(")\n");

}

String providers = builder.toString();

//now display the string on the screen or in the logs for debugging.

Below you can find the output of a running Android 4.4 in an emulator with Google Play APIs, after the security provider has been patched:

provider: GmsCore_OpenSSL1.0 (Android's OpenSSL-backed security provider)

provider: AndroidOpenSSL1.0 (Android's OpenSSL-backed security provider)

provider: DRLCertFactory1.0 (ASN.1, DER, PkiPath, PKCS7)

provider: BC1.49 (BouncyCastle Security Provider v1.49)

provider: Crypto1.0 (HARMONY (SHA1 digest; SecureRandom; SHA1withDSA signature))

provider: HarmonyJSSE1.0 (Harmony JSSE Provider)

provider: AndroidKeyStore1.0 (Android KeyStore security provider)

For some applications that support older versions of Android, bundling an up-to-date library may be the only option. Spongy Castle (a repackaged version of Bouncy Castle) is a common choice in these situations. Repackaging is necessary because Bouncy Castle is included in the Android SDK. The latest version of Spongy Castle likely fixes issues encountered in the earlier versions of Bouncy Castle that were included in Android. Note that the Bouncy Castle libraries packed with Android are often not as complete as their counterparts from the legion of the Bouncy Castle. Lastly: bear in mind that packing large libraries such as Spongy Castle will often lead to a multidexed Android application.

Android SDK provides mechanisms for specifying secure key generation and use. Android 6.0 (Marshmallow, API 23) introduced the KeyGenParameterSpec class that can be used to ensure the correct key usage in the application.

Here's an example of using AES/CBC/PKCS7Padding on API 23+:

String keyAlias = "MySecretKey";

KeyGenParameterSpec keyGenParameterSpec = new KeyGenParameterSpec.Builder(keyAlias,

KeyProperties.PURPOSE_ENCRYPT | KeyProperties.PURPOSE_DECRYPT)

.setBlockModes(KeyProperties.BLOCK_MODE_CBC)

.setEncryptionPaddings(KeyProperties.ENCRYPTION_PADDING_PKCS7)

.setRandomizedEncryptionRequired(true)

.build();

KeyGenerator keyGenerator = KeyGenerator.getInstance(KeyProperties.KEY_ALGORITHM_AES,

"AndroidKeyStore");

keyGenerator.init(keyGenParameterSpec);

SecretKey secretKey = keyGenerator.generateKey();

The KeyGenParameterSpec indicates that the key can be used for encryption and decryption, but not for other purposes, such as signing or verifying. It further specifies the block mode (CBC), padding (PKCS7), and explicitly specifies that randomized encryption is required (this is the default.) "AndroidKeyStore" is the name of the cryptographic service provider used in this example.

GCM is another AES block mode that provides additional security benefits over other, older modes. In addition to being cryptographically more secure, it also provides authentication. When using CBC (and other modes), authentication would need to be performed separately, using HMACs (see the Reverse Engineering chapter). Note that GCM is the only mode of AES that does not support paddings.

Attempting to use the generated key in violation of the above spec would result in a security exception.

Here's an example of using that key to encrypt:

String AES_MODE = KeyProperties.KEY_ALGORITHM_AES

+ "/" + KeyProperties.BLOCK_MODE_CBC

+ "/" + KeyProperties.ENCRYPTION_PADDING_PKCS7;

KeyStore keyStore = KeyStore.getInstance("AndroidKeyStore");

// byte[] input

Key key = keyStore.getKey(keyAlias, null);

Cipher cipher = Cipher.getInstance(AES_MODE);

cipher.init(Cipher.ENCRYPT_MODE, key);

byte[] encryptedBytes = cipher.doFinal(input);

byte[] iv = cipher.getIV();

// save both the iv and the encryptedBytes

Both the IV (initialization vector) and the encrypted bytes need to be stored; otherwise decryption is not possible.

Here's how that cipher text would be decrypted. The input is the encrypted byte array and iv is the initialization vector from the encryption step:

// byte[] input

// byte[] iv

Key key = keyStore.getKey(AES_KEY_ALIAS, null);

Cipher cipher = Cipher.getInstance(AES_MODE);

IvParameterSpec params = new IvParameterSpec(iv);

cipher.init(Cipher.DECRYPT_MODE, key, params);

byte[] result = cipher.doFinal(input);

Since the IV is randomly generated each time, it should be saved along with the cipher text (encryptedBytes) in order to decrypt it later.

Prior to Android 6.0, AES key generation was not supported. As a result, many implementations chose to use RSA and generated a public-private key pair for asymmetric encryption using KeyPairGeneratorSpec or used SecureRandom to generate AES keys.

Here's an example of KeyPairGenerator and KeyPairGeneratorSpec used to create the RSA key pair:

Date startDate = Calendar.getInstance().getTime();

Calendar endCalendar = Calendar.getInstance();

endCalendar.add(Calendar.YEAR, 1);

Date endDate = endCalendar.getTime();

KeyPairGeneratorSpec keyPairGeneratorSpec = new KeyPairGeneratorSpec.Builder(context)

.setAlias(RSA_KEY_ALIAS)

.setKeySize(4096)

.setSubject(new X500Principal("CN=" + RSA_KEY_ALIAS))

.setSerialNumber(BigInteger.ONE)

.setStartDate(startDate)

.setEndDate(endDate)

.build();

KeyPairGenerator keyPairGenerator = KeyPairGenerator.getInstance("RSA",

"AndroidKeyStore");

keyPairGenerator.initialize(keyPairGeneratorSpec);

KeyPair keyPair = keyPairGenerator.generateKeyPair();

This sample creates the RSA key pair with a key size of 4096-bit (i.e. modulus size).

Static Analysis

Locate uses of the cryptographic primitives in code. Some of the most frequently used classes and interfaces:

CipherMacMessageDigestSignatureKey,PrivateKey,PublicKey,SecretKey- And a few others in the

java.security.*andjavax.crypto.*packages.

Ensure that the best practices outlined in the "Cryptography for Mobile Apps" chapter are followed. Verify that the configuration of cryptographic algorithms used are aligned with best practices from NIST and BSI and are considered as strong.

Testing Random Number Generation

Overview

Cryptography requires secure pseudo random number generation (PRNG). Standard Java classes do not provide sufficient randomness and in fact may make it possible for an attacker to guess the next value that will be generated, and use this guess to impersonate another user or access sensitive information.

In general, SecureRandom should be used. However, if the Android versions below KitKat are supported, additional care needs to be taken in order to work around the bug in Jelly Bean (Android 4.1-4.3) versions that failed to properly initialize the PRNG.

Most developers should instantiate SecureRandom via the default constructor without any arguments. Other constructors are for more advanced uses and, if used incorrectly, can lead to decreased randomness and security. The PRNG provider backing SecureRandom uses the /dev/urandom device file as the source of randomness by default [#nelenkov].

Static Analysis

Identify all the instances of random number generators and look for either custom or known insecure java.util.Random class. This class produces an identical sequence of numbers for each given seed value; consequently, the sequence of numbers is predictable.

The following sample source code shows weak random number generation:

import java.util.Random;

// ...

Random number = new Random(123L);

//...

for (int i = 0; i < 20; i++) {

// Generate another random integer in the range [0, 20]

int n = number.nextInt(21);

System.out.println(n);

}

Instead a well-vetted algorithm should be used that is currently considered to be strong by experts in the field, and select well-tested implementations with adequate length seeds.

Identify all instances of SecureRandom that are not created using the default constructor. Specifying the seed value may reduce randomness. Prefer the no-argument constructor of SecureRandom that uses the system-specified seed value to generate a 128-byte-long random number.

In general, if a PRNG is not advertised as being cryptographically secure (e.g. java.util.Random), then it is probably a statistical PRNG and should not be used in security-sensitive contexts.

Pseudo-random number generators can produce predictable numbers if the generator is known and the seed can be guessed. A 128-bit seed is a good starting point for producing a "random enough" number.

The following sample source code shows the generation of a secure random number:

import java.security.SecureRandom;

import java.security.NoSuchAlgorithmException;

// ...

public static void main (String args[]) {

SecureRandom number = new SecureRandom();

// Generate 20 integers 0..20

for (int i = 0; i < 20; i++) {

System.out.println(number.nextInt(21));

}

}

Dynamic Analysis

Once an attacker is knowing what type of weak pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) is used, it can be trivial to write proof-of-concept to generate the next random value based on previously observed ones, as it was done for Java Random. In case of very weak custom random generators it may be possible to observe the pattern statistically. Although the recommended approach would anyway be to decompile the APK and inspect the algorithm (see Static Analysis).

References

- [#nelenkov] - N. Elenkov, Android Security Internals, No Starch Press, 2014, Chapter 5.

OWASP MASVS

- V3.6: "All random values are generated using a sufficiently secure random number generator."

OWASP Mobile Top 10 2016

- M6 - Broken Cryptography

CWE

- CWE-330: Use of Insufficiently Random Values

Testing Key Management

Overview

Symmetric cryptography provides confidentiality and integrity of data because it ensures one basic cryptographic principle. It is based on the fact that a given ciphertext can only, in any circumstance, be decrypted when providing the original encryption key. The security problem is thereby shifted to securing the key instead of the content that is now securely encrypted. Asymmetric cryptography solves this problem by introducing the concept of a private and public key pair. The public key can be distributed freely, the private key is kept secret.

When testing an Android application on correct usage of cryptography it is thereby also important to make sure that key material is securely generated and stored. In this section we will discuss different ways to manage cryptographic keys and how to test for them. We discuss the most secure way, down to the less secure way of generating and storing key material.

The most secure way of handling key material, is simply never storing it on the filesystem. This means that the user should be prompted to input a passphrase every time the application needs to perform a cryptographic operation. Although this is not the ideal implementation from a user experience point of view, it is however the most secure way of handling key material. The reason is because key material will only be available in an array in memory while it is being used. Once the key is not needed anymore, the array can be zeroed out. This minimizes the attack window as good as possible. No key material touches the filesystem and no passphrase is stored. However, note that some ciphers do not properly clean up their byte-arrays. For instance, the AES Cipher in BouncyCastle does not always clean up its latest working key.

The encryption key can be generated from the passphrase by using the Password Based Key Derivation Function version 2 (PBKDFv2). This cryptographic protocol is designed to generate secure and non brute-forceable keys. The code listing below illustrates how to generate a strong encryption key based on a password.

public static SecretKey generateStrongAESKey(char[] password, int keyLength)

{

//Initiliaze objects and variables for later use

int iterationCount = 10000;

int saltLength = keyLength / 8;

SecureRandom random = new SecureRandom();

//Generate the salt

byte[] salt = new byte[saltLength];

randomb.nextBytes(salt);

KeySpec keySpec = new PBEKeySpec(password.toCharArray(), salt, iterationCount, keyLength);

SecretKeyFactory keyFactory = SecretKeyFactory.getInstance("PBKDF2WithHmacSHA1");

byte[] keyBytes = keyFactory.generateSecret(keySpec).getEncoded();

return new SecretKeySpec(keyBytes, "AES");

}

The above method requires a character array containing the password and the needed keylength in bits, for instance a 128 or 256-bit AES key. We define an iteration count of 10000 rounds which will be used by the PBKDFv2 algorithm. This significantly increases the workload for a bruteforce attack. We define the salt size equal to the key length, we divide by 8 to take care of the bit to byte conversion. We use the SecureRandom class to randomly generate a salt. Obviously, the salt is something you want to keep constant to ensure the same encryption key is generated time after time for the same supplied password. Storing the salt does not need any additional security measures, this can be publicly stored in the SharedPreferences without the need of any encryption. Afterwards the Password-based Encryption (PBE) key is generated using the recommended PBKDF2WithHmacSHA1 algorithm.

Now, it is clear that regularly prompting the user for its passphrase is not something that works for every application. In that case make sure you use the Android KeyStore API. This API has been specifically developed to provide a secure storage for key material. Only your application has access to the keys that it generates. Starting from Android 6.0 it is also enforced that the KeyStore is hardware-backed. This means a dedicated cryptography chip or trusted platform module (TPM) is being used to secure the key material.

However, be aware that the KeyStore API has been changed significantly throughout various versions of Android. In earlier versions the KeyStore API only supported storing public\private key pairs (e.g., RSA). Symmetric key support has only been added since API level 23. As a result, a developer needs to take care when he wants to securely store symmetric keys on different Android API levels. In order to securely store symmetric keys, on devices running on Android API level 22 or lower, we need to generate a public/private key pair. We encrypt the symmetric key using the public key and store the private key in the KeyStore. The encrypted symmetric key can now be safely stored in the SharedPreferences. Whenever we need the symmetric key, the application retrieves the private key from the KeyStore and decrypts the symmetric key.

A sligthly less secure way of storing encryption keys, is in the SharedPreferences of Android. When SharedPreferences are initialized in MODE_PRIVATE, the file is only readable by the application that created it. However, on rooted devices any other application with root access can simply read the SharedPreference file of other apps, it does not matter whether MODE_PRIVATE has been used or not. This is not the case for the KeyStore. Since KeyStore access is managed on kernel level, which needs considerably more work and skill to bypass without the KeyStore clearing or destroying the keys.

The last two options are to use hardcoded encryption keys in the source code and storing generated keys in public places like /sdcard/. Obviously, hardcoded encryption keys are not the way to go. This means every instance of the application uses the same encryption key. An attacker needs only to do the work once, to extract the key from the source code . Consequrently, he can decrypt any other data that he can obtain and that was encrypted by the application. Lastly, storing encryption keys publicly also is highly discouraged as other applications can have permission to read the public partition and steal the keys.

Static Analysis

Locate uses of the cryptographic primitives in reverse engineered or disassembled code. Some of the most frequently used classes and interfaces:

CipherMacMessageDigestSignatureKeyStoreKey,PrivateKey,PublicKey,SecretKeySpec- And a few others in the

java.security.*andjavax.crypto.*packages.

As an example we illustrate how to locate the use of a hardcoded encryption key. First disassmble the DEX bytecode to a collection of Smali bytecode files using Baksmali.

$ baksmali d file.apk -o smali_output/

Now that we have a collection of Smali bytecode files, we can search the files for the usage of the SecretKeySpec class. We do this by simply recursively grepping on the Smali source code we just obtained. Please note that class descriptors in Smali start with L and end with ;:

$ grep -r "Ljavax\crypto\spec\SecretKeySpec;"

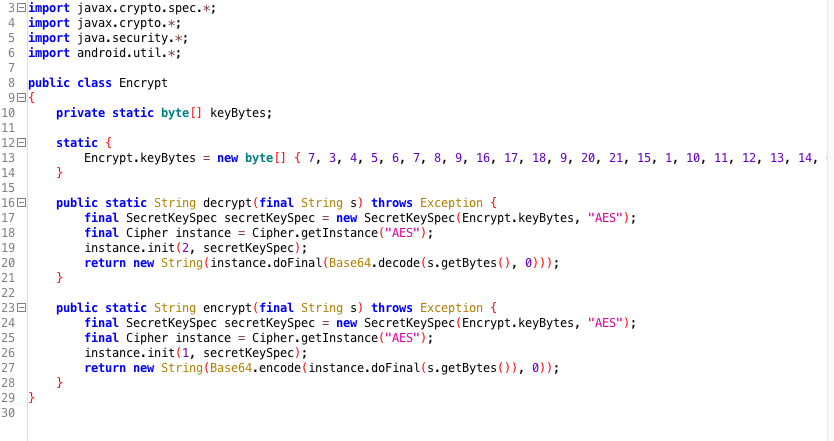

This will highlight all the classes that use the SecretKeySpec class, we now examine all the highlighted files and trace which bytes are used to pass the key material. The figure below shows the result of performing this assessment on a production ready application. For sake of readability we have reverse engineered the DEX bytecode to Java code. We can clearly locate the use of a static encryption key that is hardcoded and initialized in the static byte array Encrypt.keyBytes.

Dynamic Analysis

Hook cryptographic methods and analyze the keys that are being used. Monitor file system access while cryptographic operations are being performed to assess where key material is written to or read from.

References

OWASP Mobile Top 10

- M6 - Broken Cryptography

OWASP MASVS

- V3.1: "The app does not rely on symmetric cryptography with hardcoded keys as a sole method of encryption."

- V3.3: "The app uses cryptographic primitives that are appropriate for the particular use-case, configured with parameters that adhere to industry best practices."

- V3.5: "The app doesn't reuse the same cryptographic key for multiple purposes."

- V3.6: "All random values are generated using a sufficiently secure random number generator."

CWE

- CWE-321: Use of Hard-coded Cryptographic Key

- CWE-326: Inadequate Encryption Strength